New York Times

NONFICTION

Through the Russian Wilderness in Search of the World’s Largest Owl

By Tucker Malarkey

Aug. 4, 2020, 5:00 a.m. ET

OWLS OF THE EASTERN ICE

A Quest to Find and Save the World’s Largest Owl

By Jonathan C. Slaght

The wildlife biologist Jonathan Slaght first viewed the forests and mountains of the Primorye at 19 years old, when the wild terrain seemed to call him to explore and ultimately protect the inhospitable land from those who would plunder its timber, minerals and salmon. A veritable Noah’s ark of animals coexist in this extraordinary habitat: tigers, bears, leopards, moose, wild boar, sable, fox, deer, elk — and Slaght’s chosen subject, Blakiston’s fish owl. Slaght’s hope, and the premise of his engaging tale, is that uncovering the secrets of this mysterious raptor will help win it protection. In conservation, saving one species often means saving many.

Slaght’s story begins in 2005, when he teams up with a motley Russian crew to conduct research and build a conservation plan for the owls. From the warmth of an office, it sounds straightforward enough. Slaght has spent years researching wildlife in the Primorye and is well accustomed to the region’s peculiarities and privations. Still, he is not wholly prepared for what is to come.

The best time to research fish owls is winter, when the owl’s strange tracks lie etched on snowy riverbanks, and their feathers flutter visibly in bare branches. It is also a brutal season in the Russian Far East, one that continually threatens to annihilate Slaght and his team as they navigate frozen rivers and their deadly thaw, with massive cracking sheets of ice and sudden slush that could swallow man, beast and snowmobile whole.

Image

The Primorye can be pitiless, full of “quiet violence.” Those who manage to survive have been ravaged by the elements, by scarcity and by the forest itself. Deep in the woods it gets strange, and Slaght’s tireless search for owls is relieved by entertaining accounts of eccentric recluses, hunters and mystical hermits. Though “meeting a person in the woods was usually a bad thing,” Slaght observes, his crew had little choice. On their shoestring budget they need all the help they can get and repeatedly endure the social-bonding ritual of draining a bottle of vodka (or ethanol) to gain a welcome and possibly a floor to sleep on.

Mostly this is a book about the rigors of fieldwork, about cohabitating in close quarters, being stranded for weeks by storms, floods and melting ice, rejiggering strategies, “aching” immobility, malfunctioning equipment and various other misfortunes, all vividly rendered. Slaght knows this life, but he has never burrowed so deep into its dark, silent heart. We are plunged along with him into “poking thorns, prodding branches and unexpected falls,” into long frozen nights, meals of moose meat and hard candy, shredded clothes, endless paths and trails beaten, rivers forged, catastrophic weather and near-death adventures. And waiting. Lots of waiting.

Slaght has spent so much of his life waiting that waiting has long since evolved into a Zen-like state of noticing, of presence. Keeping us tucked close, we discover what it feels like to become aware of every little thing, to fully inhabit a living landscape. For this reason and others, this is an unusual (and welcome) book for our times.

Halfway through the story floats a feather from Slaght’s other life, a brief sentence about a fiancée and a wedding to plan. As if we’ve found a mango in the snow, we pause, curious. But then it’s back to the owls, and the unlikely (but very true) romance of nights waiting “in silence, like suitors,” for them to sound their enchanting synchronized duets.

The enigmatic fish owls, when they appear, are surprisingly un-owl-like, not gliding down from the trees so much as “dropping” like sacks. At a meter high, they are at once imposing and comical, a jumble of feathers with ragged, twitching ear tufts. Hunting underwater prey, they have lost their adaptation of silent flight, as well as the disk-shaped face designed for maximum audio performance. They seem endearingly awkward creatures, stalking the riverbank like hunched feathery gnomes, peering for glimmers of fish, then hurling themselves talon-first into the current.

As the team members struggle to gain a working knowledge of their subject, chasing its calls in the dark of night, scanning trees for its bulky outline, they are often humbled, their theories upended. After managing to capture and tag a good number of birds, Slaght is flummoxed that the researchers still can’t tell the male from the female. It is with heroic persistence and a bit of luck that they succeed in collecting enough data for a conservation plan. Some would run gleefully from this 20-month ordeal, but Slaght finishes the project with reluctance.

It is a testament to his talents as a writer-researcher that we appreciate why Slaght loves it here. The primal forces of the Primorye have drawn him close to his essence; to his strengths and vulnerabilities — to his impermanence. There is peace and healing to be found in such a life, and perhaps just the right balance for his soul.

After being away, Slaght writes upon his return: “I was truly comfortable here, alone among the trees, breathing in the cold air.”

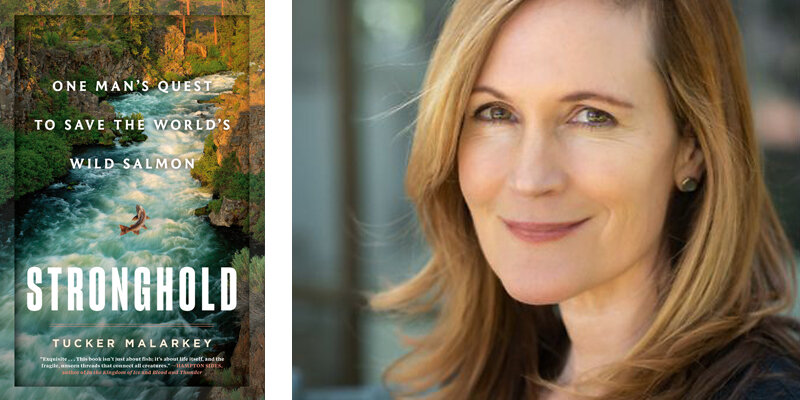

Tucker Malarkey is the author of “Stronghold: One Man’s Quest to Save the World’s Wild Salmon.”

OWLS OF THE EASTERN ICE

A Quest to Find and Save the World’s Largest Owl

By Jonathan C. Slaght

348 pp. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. $28.

Love in Quarantine, Month One

For Lucy Bidwell

Corona, Day 3

Speaking of love, I’m alone and without a plan. My son will soon be 18 and this house will soon be empty. For months I’ve tried not to feel sad or anxious about this. But those little dogs have nipped at me anyway, made me doubt where I’ve been, where I’m going. Now things have changed. We’re sheltering at home. I’m no longer alone and there are no plans. It’s just me and Elliott; the dogs, the house, the garden and more birds than I can ever remember. And time, so much time.

I go through old boxes trying to piece my life together. I’ve been meaning to do it for years, but it takes a pandemic to force me. I saved so many things; school papers, letters, notes, tickets; hard evidence that I’ve been Me since the beginning - strong, bright, broken. A creator of worlds. Something that hasn’t changed. I could always slip away, always spring the trap.

Day 7 As the days pass, we draw closer in this house. We are quiet, sensitive creatures well adapted to such conditions. I nap with my hand on my dog’s chest, his heart beating softly against my palm. Elliott drifts through the house like a cloud, flops on my bed, stares out at the trees. I no longer know what he thinks about, and marvel that I once did; that once I held him on my hip. Now he stands far above me, lean and graceful. I watch him come and go, vanish and appear like a magician, another springer of traps. We pull weeds in the garden, walk the dogs in the woods. Sometimes we talk, sometimes we don’t. There’s nothing we need to do, no pressure to be anything but us, anywhere but here. The world is constricting, retreating, suffocating. At the same time it’s expanding, gulping in new air.

And time. We agree that something strange is happening there. An hour passes, a day, a week; measures of time that no longer signify. Is it 6 pm already? Is it Sunday again? Time no longer ticks and tocks; it sloshes, back and forth, and we slosh with it, like fish in a tilting aquarium.

Day 10 Elliott turns 18 anyway. It happens, the legal end of his childhood. Soon the role that has tethered me to this house, this life for nearly two decades, will disappear like smoke. What then? I have been watching 18 approaching for years. It’s a terrifying, thrilling milestone, a moment for both of us. It’s also just another sloshing day. He won’t be celebrating with friends, there will be no party. I bake a cake and give him a Lego set, for old times sake, and to take up the time. He asks to take my car to go for a drive, just him. The love between us is strong and clear. I realize it’s okay, it’s all going to be okay. We hug to the last day of his childhood and let go.

Day 20 Birds have taken over the skies, delighted no doubt at the lack of noise and pollution. Outside my desk window, a medium sized brown bird sits perched on a branch no more than five feet away. I wait motionless for it to fly off, respecting its need to rest. Really, it must be so tiring to be a bird; all that flying around, avoiding electrical wires and cats and bigger birds. This bird is in no rush to go anywhere. I watch the movement of his eyes; it seems his blinks are slowing. Maybe he’s going to nap. Do birds nap? I thought they roosted at night. Maybe they do both. I want to know more about birds. Do they dream? The wind rustles the leaves of the maple and the bird opens his eyes and then lets his lids fall again. Just the wind.

I can’t seem to go back to work; the bird has captivated me. Beyond the maple tree is a redwood and then a birch, the wind stirring their branches. Someone is playing the violin. Not the usual house, a new player, closer, a lovely piece. Then, right in front of me, the bird drops off to sleep. I stare. Was it the violin? Now I really can’t move; this is his safe place, his shelter. I sit with him, letting the moment fill me to the brim. I’m a bit sad that I’ve never seen a bird fall asleep before. That maybe the bird was here, but I was somewhere else. No matter, it’s a new day. I will be here again tomorrow, and the next day. I will look.

Day 25 I dream of the past. It’s the boxes, bringing back lost bits of myself. In the morning the birds are loud, the full choir present. I lie in bed listening to them, wondering if my brown bird is among them. I’m not sure what day it is, but no matter. There are birds and all kinds of songs. This morning one stands out. It gives a simple two note call, over and over. I throw off sleep, stack my pillows and sit up in bed because I think I can understand it. The bird is singing the word “spir-it.” I listen for a few minutes longer to confirm. Sure enough, that’s what it’s saying. I jump out of bed and stand near the window to record it on my phone. I record it three times. No one with ears could dispute my finding. My heart is bursting. I’ve always suspected that all living creatures are just a vibration away from understanding each other. Later that day I play the recording for Elliott. “Can you hear it?” I ask. He listens, but not that hard. This is crazy mom stuff, not to be indulged. I play the recording again.

“I think it’s singing the word ‘spirit.’” Spirit, spirit, the bird sings, clear as a bell. I smile. It couldn’t be clearer.

“I can’t really hear it,” Elliott says.

I am disheartened, but only for a moment. There are things young people aren’t ready for; many things they must see and feel before they are open to receiving messages from birds. They must defend themselves from such dangerous adult notions, and rightly. The world is still treacherous and will be for some time. Reality must be laid out, tacked onto the wall like a map. Here are the dark woods, here the unknown seas, here the friendly village, the thrumming city. Here are the girls, the boys, the abstract fears. Here is my video game, my safe place, my mac and cheese. Here is the edge of my frontier, beyond which I have not ventured but must soon, whether I like it or not. No, the map must stay secure until they can locate themselves and the things they need. I forget how many years I spent doing this. The boxes brought it all back - the many anxious, self-obsessed years of absurd and pointless mental habits that I was powerless to break.

Now there are no more traps. I am a sorcerer, a conjurer of worlds. I am not in quarantine, I am napping on a branch, singing to humans in their language. So this nest will be empty. I know what to do now. I will train my ears away from teenage footfalls and boyish laughter. I will listen farther, beyond the walls and windows of this house and the boy who will leave it and I will discover a freedom I had forgotten. When this all ends, I will walk the length of Portugal. I will write stories, come up with schemes, learn about birds, maybe even fall in love again. But for now I don’t need to do any of that exhausting stuff. I just need to rest here for a while, while my life and loves find me. Who knew it, but it is all and everything I want, this long long drink, with the birds outside flying, napping, singing their messages.

Powells Books

Of Salmon and Oligarchs

by Tucker Malarkey, July 25, 2019

I remember the moment I sat up and took notice of the risks my cousin Guido Rahr was taking for fish — the same moment I started taking notes about his adventures, notes that would one day become a book. We were sitting in the grass outside our family fishing cabins on the Deschutes River where, since childhood, we had enjoyed days of wilderness and unbroken conversations. Our regular returns to the Deschutes marked our family’s time and highlighted the twists and turns of our personal journeys. Guido’s had long been the most surprising. A born hunter, he had spent his childhood stalking the high desert for snakes and lizards. Then it became fish, and his hunting ground expanded from the Deschutes to the entire Pacific Northwest. Guido pursued salmon all the way to Alaska and became one of the world’s finest fly fisherman. It was when these magnificent fish began to disappear from Oregon’s rivers that he converted his skills for catching wild creatures to humans. This unlikely outlier has since galvanized a small army of well-placed people to protect the habitat he dearly loves.

Guido was assembling his fly-fishing gear while giving me the latest update on his crusade to protect the best salmon rivers across the Pacific Rim, rivers he calls “strongholds” for the safety they offer this invaluable species as their numbers across the region decline. Like many hunters, Guido is a dedicated conservationist, for hunting grounds need protection. Guido has achieved a great deal with his stronghold mission and, against all odds, the Pacific Rim is dotted with protected areas and rivers that he and his organization, the Wild Salmon Center, have fought for from Northern California to the Russian Far East. But the future of Russia’s salmon is still uncertain — and the country is home to 40% of the world’s wild salmon. If he can't protect Russian fish, his stronghold strategy will fail.

He told me now he’d just returned from Moscow. Years of hammering away at Russia’s district and regional governments and agencies had won him both local partnership and protection for some of Kamchatka’s finest salmon rivers. But Russia was poised for rampant development in the far east, and Guido knew of plans to drill, excavate, and clear-cut the pristine region — which spelled disaster for the salmon. At this juncture, he needed to reach the people in control of such development, or those who had the resources to stop it. He needed the support of Russia’s most powerful men.

Under the surface, he was still an obsessive hunter, and he had set his sights on the most challenging and mysterious quarry to date.He told me that through one of his high-level connections, he’d just met with the Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska and asked directly if he would help protect Russia’s salmon. The story alarmed me. I had studied Soviet Russia in college and knew something of the dark complexities of its power elite. Did Guido know what he was doing?

In 2006, Oleg Deripaska had a net worth of 28 billion dollars. From modest means, and with a background in theoretical physics, Deripaska had consolidated his positions and holdings in the consortium Russian Aluminum, during the so-called “aluminum wars,” in which men vying for control of the lucrative industry “disappeared.” There were also allegations, according to the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, that Deripaska bribed government officials and had links to organized crime. While this was business as usual in Russia, the Treasury Department had repeatedly denied Deripaska a visa to the U.S., the free-market haven where many oligarchs romped. Deripaska had taken the meeting with Guido not because he was a fisherman or an environmentalist, but because he had a PR problem in the west. Deripaska was looking to improve his reputation — whether helping an American conservationist would do the trick was anyone’s guess.

But Guido had to try. As he told the story, I noted an undercurrent of fear and excitement running through him, flashing in his blue eyes. I knew him well enough to see that Guido had encountered entirely unfamiliar terrain, and it activated him to the core. I realized that, at 46, Guido had not changed at all. Under the surface, he was still an obsessive hunter, and he had set his sights on the most challenging and mysterious quarry to date.

Guido didn’t totally understand the “in” that had cracked open the door to Deripaska, but he dove through it anyway. Headlong. He flew to Moscow, deciding that for Deripaska he would use the deceptively simple strategy that had worked for him in the past: ask for what you want. The problem was, he knew little of Deripaska, or of oligarchs in general. How did such men operate, and how much power did they really have? More to the point, how much could he ask of Deripaska? By the time he landed, Guido determined he would ask for everything he wanted.

The meeting took place at one of the satellite airports outside Moscow, where Deripaska was flying in from Asia in his Gulfstream V-SP. Deripaska arrived right on time. He was big-boned and tall, and his pale blue eyes were large, keen, and on the cool side. This, Guido saw, was an apex predator. What he fed on, he had no idea. But he knew enough about such men to keep things short and to the point. He watched as the oligarch sat down, crossed his long legs, and turned his pale, sharp eyes on Guido. “Okay, Guida,” he said. “What do you want from me?”

Guido, ignoring the mispronunciation, presented a map of the Russian Far East with its myriad rivers and explained to Deripaska the importance of salmon conservation. In the west, they had lost their best salmon rivers due to ignorance and mismanagement. Once salmon rivers had been so badly degraded, it was nearly impossible to restore them. Russia was in possession of the most pristine salmon ecosystem in the world, a veritable protein factory that could feed millions of people and nourish a massive ecosystem. But, Guido said, the decision to save these pristine watersheds was a Russian one. Which was why Guido was here. He added that the Wild Salmon Center had been partnering with Russian scientists and Moscow State University and the Academy of Sciences had sanctioned the stronghold program in the Russian Far East.

Deripaska listened as Guido went on, telling the oligarch that he needed a few things from him: his money, his contacts, and his political clout to navigate the Russian federal government and provide more support for the local conservation groups. Lastly, he needed him to help stop the logging on the pristine Samarga River, where Guido had just returned from. Then he shut up while Deripaska studied the map. The oligarch thought for a moment and said, “Okay. I will help you. I’m going to give you some introductions and some funding. I will also give you this guy who works for me, and he’s going to help you do all these things.”

Guido rose, shook Deripaska’s hand. A moment later, the oligarch was gone. So that was how it worked, Guido thought. Boom, boom, boom, like pool balls clicking against each other, or dominos falling. It was a world away from the protracted, fraught conservation battles in the west, which were more like a tangle of string.

Guido left with adrenaline pumping in his veins, cautiously excited that Deripaska’s words would amount to something, and that the meeting wouldn’t come back to bite him either. In a country where a few men controlled entire industries, the fate of an ecosystem lay in a phone call.

Done with his recounting, Guido was ready to hit the river, where he would think about it all further. Perhaps conservation in this country wasn’t impossible after all, he told me, gathering his gear. I watched him disappear into the brush, knowing almost for certain that in this in this strange new hunting ground, he was going to find out. I also knew that I had to tell a story that was becoming more fantastic every year.